Asteroids: The Threat from Space

Every year, tens of thousands of meteorites fall toward Earth. Most are very small, about the size of a stone, and disintegrate in the atmosphere. Occasionally, however, asteroids are lager, sometimes stretching several kilometers in length. When these impact Earth, they create massive explosions that leave enormous craters on the planet’s surface.

4 de diciembre de 2024

Asteroids or Meteorites?

What’s the difference? Asteroids are rocky objects that drift through space, usually orbiting around a star or planet. They are too small to have the spherical shape of planets, which is caused by a planet’s gravitational pull. The largest asteroids are about 900 km in diameter, while the smallest, called meteoroids, are even smaller than a stone.

When asteroids cross a planet’s orbit, they may collide with the planet, especially in the case of meteoroids. You’ve probably seen one entering Earth’s orbit: it zooms through the atmosphere at high speed, and friction with the air causes it to heat up and ignite, leaving a bright, fleeting trail in the night sky called a shooting star. Typically, this friction causes them to burn up before reaching the ground. The rocky fragments that survive the journey through the atmosphere and reach Earth’s surface are called meteorites.

Vesta asteroid

Fragment of the asteroid Vesta that fell in Spain in May 2007.

Gibeon meteorite

Fragment of the Gibeon meteorite, weighing 4.5 kg and measuring 19 cm across. It was found in Australia in 1991.

What we call shooting stars are actually meteoroids entering Earth’s atmosphere and igniting. The fragments that survive and reach the Earth’s surface are called meteorites.

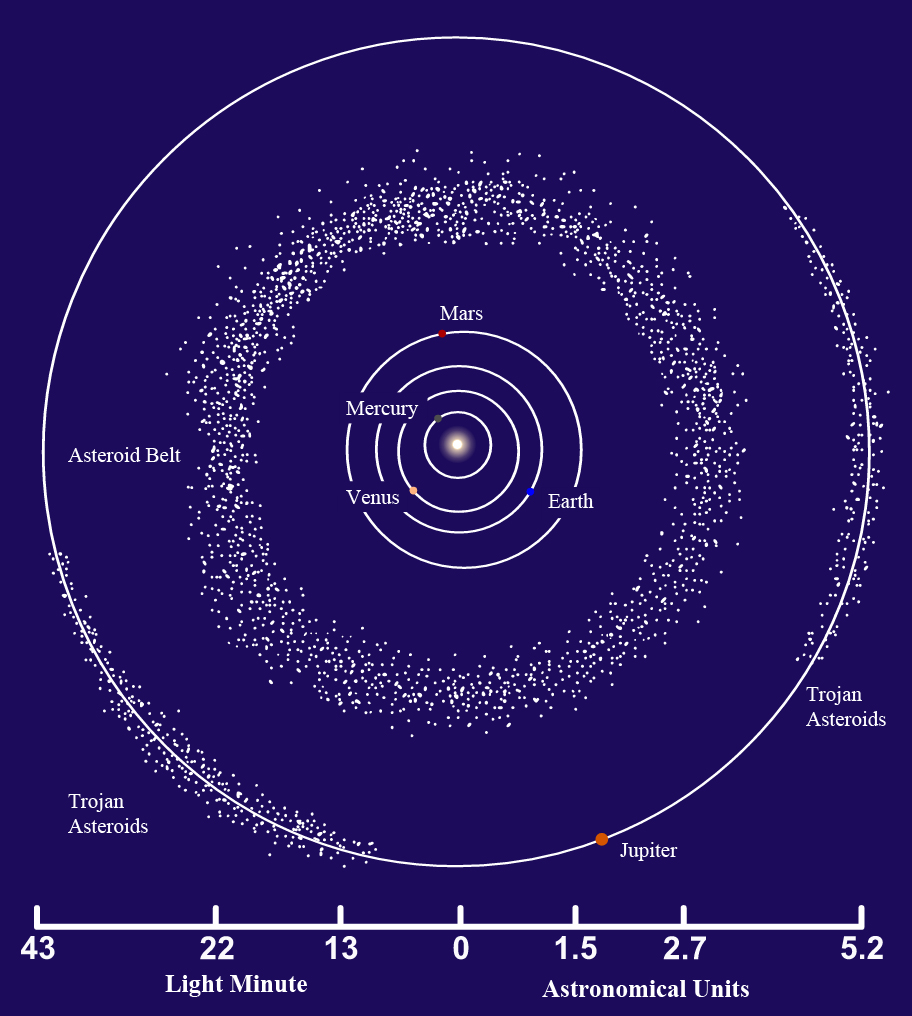

Where Are Asteroids Located?

There’s a belt between Mars and Jupiter packed with asteroids orbiting the Sun. Most of the solar system’s asteroids are found there. There are millions of them, many measuring over 1 km in diameter, but their combined mass is less than 6% of the Moon’s mass. Their orbits around the Sun are stable, but some are deflected and cross the paths of planets.

This asteroid belt is believed to have formed due to Jupiter’s immense gravitational pull. During the early stages of the solar system, this force was so strong that it prevented these fragments from coming together to form another planet. However, not all asteroids are confined to this belt. Some orbit planets and are called Trojans. Jupiter, having the strongest gravitational pull of any planet in the solar system, has the most Trojans. Beyond the asteroid belt, among the giant planets, are other asteroids known as Centaurs.

Finally, some asteroids, classified as NEO (Near Earth Objects) are of great interest because they come close to Earth. Their orbits intersect with ours, so they are closely monitored…

Planetary Scars

When an asteroid collides with a planet, it creates a crater. The size of the crater depends on the asteroid’s size, composition, and trajectory. For example, an object a few dozen meters in diameter can produce an explosion far more powerful than an atomic bomb.

Today, tens of thousands of meteorites hit Earth each year. Today, tens of thousands of meteorites hit Earth each year. This might seem significant, but it’s far less frequent than during the early solar system. Back then, planets endured relentless asteroid bombardment. The Moon’s surface, covered in craters, is a testament to this period of heavy impacts.

So, why doesn’t Earth’s surface resemble the Moon’s with its countless craters and distinctive Swiss cheese appearance? The answer lies in erosion—a process nearly absent on our satellite. Erosion is the gradual wearing away of surfaces caused by air, water, and living organisms on the planet. Together, these forces can erase geological scars from Earth’s surface. For example, over hundreds of millions of years, erosion could flatten the Pyrenees and transform them into a plain.

Barringer crater in Arizona (USA) is 1,200 m in diameter and was caused by a fairly large meteorite impact about 20,000 years ago. It’s one of the few recent craters to have survived the fierce effects of erosion on the Earth’s surface. In contrast, thousands of craters remain visible on the Moon, preserved by its lack of erosion.

Impacts with Earth

During the early stages of Earth’s formation, intense asteroid showers were common. Overtime, these impacts became less frequent, allowing life to emerge. The last major impact—so powerful it caused all ocean water to boil and evaporate—is thought to have occurred around 4 billion years ago. Water on Earth has remained in liquid form since then, a necessary condition for the appearance and sustainment of life as we know it.

Impacts, however, continued. The most famous one occurred 65 million years ago near present-day Mexico. It contributed to the extinction of the dinosaurs. This impact unleashed an explosion more powerful than dozens of thermonuclear bombs combined, throwing large amounts of dusty debris and vapor into the atmosphere and blocking sunlight for an extended period.

Smaller asteroids still hit Earth regularly. Astronomers continuously scan the night sky and calculate the paths followed by the objects nearest to Earth. Recently, they identified a large asteroid expected to pass very close to Earth in 2029. This is not science fiction—it’s a reminder of the importance of monitoring asteroids.

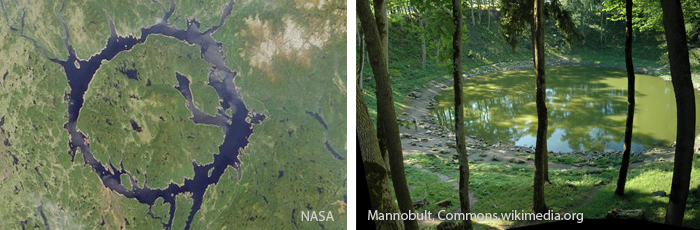

The Manicouagan Lake in Quebec, formed 212 million years ago when a large meteorite collided with Earth.

In Kaali, Estonia, nine craters were created by the impact of a single meteorite that split into several fragments before reaching the surface. These craters, estimated to have formed more than 9,900 years ago, remain a subject of scientific study today.

The most famous asteroid impact is the one believed to have contributed to the extinction of the dinosaurs. This event occurred near what is now Mexico about 65 million years ago.

The Mysterious Tunguska Incident

At 7:17 a.m. on June 30, 1908, a huge explosion lit up the skies over Tunguska, a forested region in central Siberia, Russia. The blast flattened trees and burned forests over an area larger than 2,000 km². People on horseback were knocked to the ground, and glass shattered as far as 400 km from the blast. The conductor of the Trans-Siberian Express even halted the train, fearing derailment.

The energy from the blast has been estimated at 10 to 15 megatons—far more powerful than the 0.015 megatons released by the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

Strangely, no crater was formed. Scientists now believe that the explosion occurred approximately 8 km above the surface, likely due to a meteorite about 80 meters in diameter that disintegrated in mid-air. Composed mostly of ice, the meteorite was probably a fragment of a comet. Similar events have been reported since then.

An Asteroid Approaches Earth

Currently, about 10,000 objects roaming in space are classified as NEOs. When one of these bodies comes within 0.05 Astronomical Units (7.5 million kilometers) of Earth, it is labeled a Potentially Hazardous Object (PHA). The name is fitting: an impact from one of these objects would have devastating consequences for our civilization. To date, about 2,400 objects PHAs have been identified. One of these, Apophis, caused significant concern when it was discovered.

Astronomers calculated that this large asteroid would pass close to Earth around the year 2036. Initially, scientists believed it wouldn’t collide with Earth but could come close enough to cause significant damage. The alarm sparked efforts to develop strategies for diverting the asteroid. Fortunately, further calculations have confirmed that Apophis poses no threat.

Currently, the asteroid considered the greatest risk is Bennu. However, the chance of Bennu impacting Earth in the year 2182 is just 0.037%. While no asteroid poses a serious threat right now, it’s still wise to remain prepared for the possibility. After all, an asteroid large enough to cause significant damage impacts Earth about once every 40,000 years.

The Moon is believed to have formed when a massive asteroid struck Earth, ejecting a fragment that eventually became locked in orbit around the planet.

Asteroids or Planets?

Some rocky bodies in the solar system are too large to be considered asteroids but not large enough to qualify as planets. Pluto, lurking in the outer fringes of the solar system, is a prime example. Until recently, Pluto was classified as a planet, even though it is smaller than the Moon. Astronomers addressed this issue by introducing a new category: dwarf planets. In August 2006, Pluto, along with Ceres and Eris—both previously categorized as asteroids—was officially designated a dwarf planet.

Ceres

Pluto

Dwarf planets don’t exert much gravitational influence on nearby smaller objects. They aren’t large enough to clear their orbits of other objects, unlike classical planets, which do so through their gravitational pull.

Was Life Hitching a Ride on Meteorites?

Is it possible that we are all aliens? This intriguing question lies at the heart of panspermia, a scientific hypothesis suggesting that life may have arrived on Earth via meteorites. While the theory is not widely accepted, it has gained some experimental support in recent years. Jacek Wierzchos, a researcher at the Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales – CSIC (Spain), participated in the experiment.

In 2007, a sample of lichens and microorganisms was sent into space aboard the Photon M3 spacecraft, launched from Baikonur, Kazakhstan. When the spacecraft returned to Earth two weeks later, the organisms were still alive. “If organisms can survive a trip through space, we can’t rule out the possibility that life reached Earth from space,” Wierzchos explained.

Maybe life did not reach Earth travelling inside meteorites, but a large amount of organic matter—the type of matter that living organisms are made of—has definitely reached and continues to reach Earth, carried inside meteorites since the planet’s formation.

Image of the 43 scientific and technological devices contained in the Photon M3 capsule.

WRITTEN BY Héctor Ruiz Martín

@hruizmartin

Pictures & Illustrations credits

- Meteorite approaching Earth – Johan Swanepoel @123rf.com.

- Ida asteroid – NASA-JPL.

- Vesta asteroid – STSCI, B- Zellner, NASA.

- Gibeon meteorite – H. Raab, Commons Wikimedia.org.

- Asteroid belt – NASA-JPL.

- Barringer crater – D. Roddy (U.S. Geological Survey), Lunar and Planetary Institute.

- Manicouagan Lake, Quebec – NASA.

- Kaali craters, Estonia – Mannobult, Commons Wikimedia.org.

- Dinosaurs – Esteban De Armas @123rf.com

- Tunguska event – Commons Wikimedia.org.

- Asteroid approaching Earth – Romolo Tavani, @123rf.com

- Ceres – Justin Cowart

- Pluto – NASA, Johns Hopkins University, Applied Physics Laboratory, Southwest Research Institute.

- Photon M3 – ESA – S. Corvaja 2007

Very nice and informative. Please send more information on meteorites and other objects. Thank you